For the longest time, irrigated High-Yielding Variety (HYV) rice has been Abdul Hamid’s primary source of income like many others. But for the last five years, he planted only half the amount that he did in the previous years. The HYV rice is extremely wa• ter-consuming to grow. During harvest time, Hamid experienced terrible water crisis and had to buy water with high price but receivedminimal return at the end.

Hamid, a father of three daughters often worked in the rice field from eight in the morning until two in the afternoon. He lives in the high BarindTract, a region that has a dis• tinctive physiographic feature comprising a series of uplifted blocks of terraced land cov• ering 8,720 km2 in northwestern Bangladesh.

In the area, averagerainfall is comparatively low with irregular distribution while temperature during the monsoon season is very high. The area is semi-arid and drought-prone, and has low-fertile, red colored, harsh and hard soil.

With the introduction of the green revolution in the mid-1960s, farmers started cultivation of chemically dependent HYV irrigated rice in great extent by increased irrigation facilities using underground water through deep tube wells. In four decades of excessive use of ground water for HYV rice irrigation, ground water level has dropped up to 120-1 50 feet from the surface.

Such practice created manifold problems in farming, biodiversity and livelihood. Many deep tube wells have now collapsed and this situation further deteriorated in that even drinking water become scarce in certain villages of the region. Like many other farmers, Hamid, a marginal farmer from Bohora Village of Kol ma Union of Tanure Upazila under Rajshahi District, was grappling with the impact of extreme weather events like drought.

Until five years ago, on his one-hectare land, he grew only rice throughout the year and a little wheat during Rabi (October to March) season. His income was so low that he could hardly make ends meet. He didn’t own any livestock and was completely dependent on chemical fertilisers and pesticides for farming, which slowly became unaffordable for him due to rising prices. Practicing mono-cropping and continued use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides adversely affected his land’s soil quality, causing low productivity. Living from hand to mouth, he almost planned to leave farming forever.

But it was also five years ago, in 2014, when Hamid started to venture into vermicomposting. And nobody imagined that this small initiative would one day change his life and the drought-affected community. Hard work and good guidance can make all the difference in life, as in his case.

Life-changingVermicomposting

Further back in 2012, Hamid attended a programme organised by BARCIKin his village, where he learned about integrated farming systems and several techniques such as intercropping, seed conservation, as well as preparations of bio-pesticides and vermicomposting that could increase soil fertility. He found the idea of preparing organic manure quite appealing. But he was initially apprehensive,not knowing how to start and since he didn’t own any cattle. BARCIK’sstaff assuaged his worries and taught him ways to do vermicomposting, for example,by collecting cow dung scattered around the village.

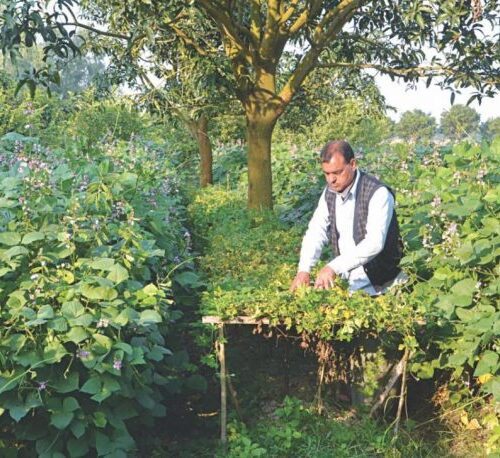

And this is exactly what Hamid did. Every morning he collected cow droppings that fell on the streets or in open spaces and gathered them in the courtyard. With support from BARCIK, he got a vermi bed installed, a base required to put the waste for the preparation of manure.

“Once I started manufacturing vermicompost, I never looked back,” Hamid said. He now collects and purchases cow dung for organic manure. With 24 vermi beds, his is now able to produce and sell eight to nine hundred kilograms of vermicompost per month. In five years, he has become an expert in vermicomposting. He has even begun to supply compost worms, about 1,500,000, to at least 350 farmers in 15 villages and also trained them on preparing organic manure.

Practicing integrated farming

Through the knowledge-sharing and exchange learning vrsits arranged by BARCIK, he acquired different techniques of sustainable integrated farming. Hamid now practices mixed cropping of papaya, bean, brinjal, red amaranth, spices in rabi season (end of monsoon) and ladies’ fingers, and cucurbits in kharif (beginning of rainy season). He also has a kitchen garden that ensures supply of vegetables around the year.

“Life has truly changed for us,” said Hamid smiling. “Till a few years back, it was hard to arrange meal for thrice a day but these days we are successfully managing our field, cultivating a flourishing kitchen garden and have learned superior techniques of growing food. Also, making vermicompost has proved to be a real boon.”

By successfully adopting integrated farming, Hamid’s dependence on the market for farm inputs has been reduced. He is very capable in preparing bio-pesticides using plant extracts and local biodegradable ingredients. He doesn’t use chemical fertilisers and pesticides anymore and this has helped reduce cost of cultivation and improved his farm’s soil health.

Last year he received training on plant nursery establishment and produced papaya seedlings that neighbors buy from him. He also distributed some native varieties of saplings to people who love native species so they can plant in their villages. Moreover, he was often called upon by other local NGO’s to conduct hands-on training sessions on vermicomposting for their beneficiaries.

Increased economic capacity and social acceptance

On an average Hamid has been earning BOT 12000 to 13000 (140 to 152 USO) monthly by selling vermin compost and earthworms that made him quite capable to financially provide for his family. He has recently refurbished his house and installed a sanitary latrine and a 100-watt solar energysystem on the roof of his house which powers four bulbs, one television and rechargesmobile phones.

Hamid, who used to be poor, has set an example for his village and earned respect for his hard work. He is being invited to different programs arranged by the Department of Agricultural Extension,Department of Youth, and Social Welfare and Local Developmentto share his endeavor.He takes part in several agricultural fairs to promote vermicompost. He evenmanagedto stop five child marriages in his village. “Though I don’t have sufficient land and resources,I am still able to influence others. I am happy with my dignified life,” said proud Hamid.

Fertile and sustainable

Hamid’s initiative has turned barren lands into fertile and greener farms. Villagers come forward to assert the practice of mix-cropping in lieu of HYV rice cultivation that certainly helps to retain ground water level. Hamid was able to change the outlook of farmers on sustainable farming and made it possible for drought-stricken but fertile low land to be cultivable through practicing agroecology.

________

Hamid is one of the success stories featured in “The Enduring Narratives of Agroecology” by IPAM & PANAP.