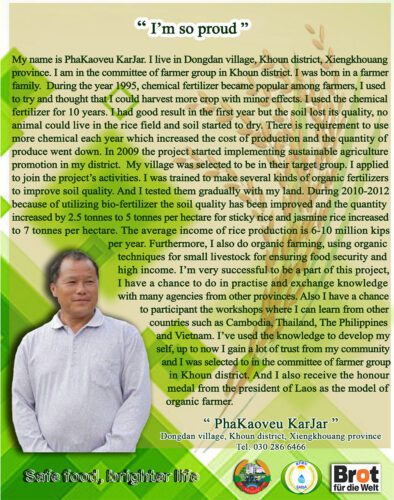

““I thought I could harvest more crops with minor effects,” admits PhaKaoveu Karjar, a farmer from Dongdan village in the district of Khoun.

It was 1995, and the use of chemicals was popular among the farmers then. PhaKaoveu experienced good results in his first year of chemical application, however over the next nine years, he saw the quality of the soil in his farm deteriorating. No animal could live in the rice fields. Every year he needed to buy more chemical inputs, increasing the cost of his production, but which did nothing to arrest his steadily decreasing yield. PhaKaoveu learned firsthand the pesticide trap and productivity myth sold by chemical agriculture.

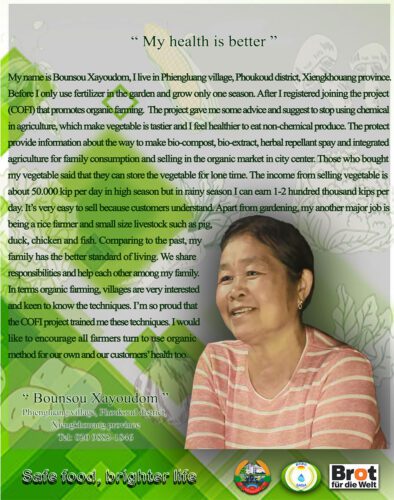

Bounsou Xayoudom, a farmer from Phiengluang village in the Phoukoud district, was in a similarly ironic situation. She used chemical fertilizer to improve her yield but could grow only one season. When she joined the program of Sustainable Agriculture and Environment Development Association (SAEDA) on the commercialization and institutionalization of organic farming, she was immediately told to stop using chemicals. Doing so “made the vegetables tastier,” and she feels “healthier eating non-chemical produce.”

SAEDA’s Commercial Organic Farming and its Institutionalisation (COFI) program, in partnership with Bread of the World, was conducted across five districts in the province of Xiengkhouang, Laos PDR, which included Khoun and Phoukoud. Designed to help improve the income of smallholder farmers and provide them with better access to market opportunities, COFI trained farmer recipients in integrated agriculture, Sustainable Rice Systems, biocomposting, and the preparation of bio-extract and herbal repellents.

SAEDA’s Commercial Organic Farming and its Institutionalisation (COFI) program, in partnership with Bread of the World, was conducted across five districts in the province of Xiengkhouang, Laos PDR, which included Khoun and Phoukoud. Designed to help improve the income of smallholder farmers and provide them with better access to market opportunities, COFI trained farmer recipients in integrated agriculture, Sustainable Rice Systems, biocomposting, and the preparation of bio-extract and herbal repellents.

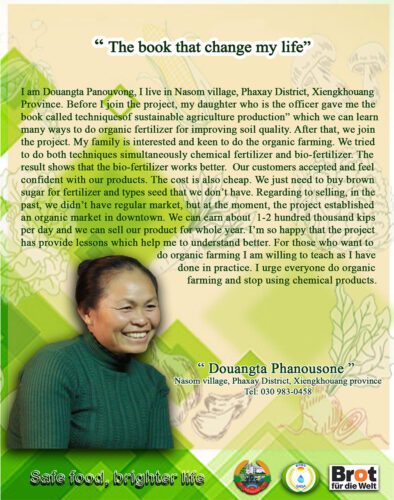

Prior to joining COFI, Douangta Panouvong, a farmer from Nasom village in Phaxay, another district in Xiengkhouang, was already interested in organic farming, after her daughter shared with her a book on techniques of sustainable agricultural production. It piqued her interest to be able to improve soil quality using natural methods. Curious, she experimented by using chemical fertilizer and bio-fertilizer simultaneously, and saw the latter outperforming the chemical-based inputs.

“The result shows that the bio-fertilizer works better,” she says. More importantly she found that organic farming was affordable and it helped that SAEDA set up an organic market in the downtown area, allowing farmers in the program to improve their income. “Our customers accepted and feel more confident about our products,” Douangta adds. She’s happy that she has the skills to grow food throughout the year, providing year-round income as well.

Bounsou, who grows food during both hot and rainy seasons and whose income has also improved with the program, agrees. “It’s very easy to sell because customers understand…. Compared to the past, my family has a better standard of living.”

Bounsou, who grows food during both hot and rainy seasons and whose income has also improved with the program, agrees. “It’s very easy to sell because customers understand…. Compared to the past, my family has a better standard of living.”

Learning how to make organic fertilizers under the program, the quality of the soil in PhaKaoveu’s farm was restored, and he saw an increase in production for his sticky rice and jasmine rice. Organic farming and livestock rearing ensure food security, while also supplementing his annual income, which has already increased from his improved rice production. He enjoys being able to exchange knowledge and learn from other organic practitioners.

As more people around them become interested in learning organic farming, all three model farmers are keen to share their knowledge and they take pride in gaining the trust of their community. “I urge everyone to do organic farming and stop using chemical products,” says Douangta.

(The stories of PhaKaoveu, Douangta, and Bounsou are adapted from the “10 Model Farmers on Organic Agriculture”, with permission from Sustainable Agriculture and Environment Development Association.)”